How sport helped lift spirits at the end of Second World War

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

Miller, who’d flown fighter planes during the Second World War, knew what real pressure was – the life and death sort, the sort now facing our brave medical staff on the coronavirus front line. There was no “pressure” in the world of bat and ball.

And just as today’s sportsmen and women hope to lift the prevailing gloom when the action resumes, Miller – nicknamed “Nugget” – came to symbolise the raising of society’s spirits through sport once the Second World War Two had finished.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

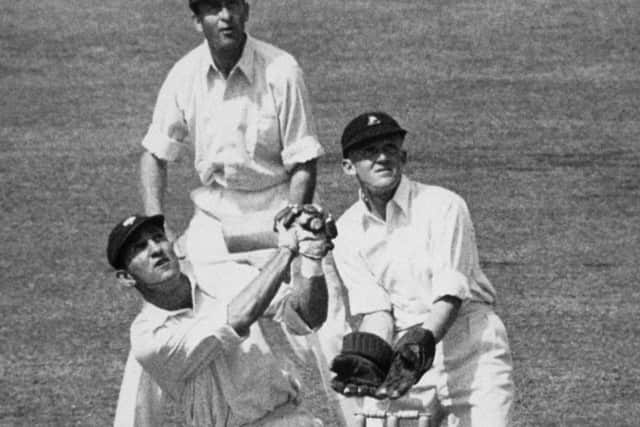

Hide AdHollywood-handsome, fearless and dashing, the sort of man that women wanted to be with and men wanted to be, “Nugget” was a key member of the Australian services team that lit up the fields of Lord’s, Old Trafford and our very own Bramall Lane in Sheffield in a series of five “Victory Tests” against England that directly followed the end of war and VE Day.

These games, played between May 19 and August 22, 1945, drew vast crowds, enormous excitement and were conducted with a palpable air of joie de vivre and gratitude, much of it supplied by the Matinee idol-esque Miller, who appreciated more than most that cricket was only a game.

The “Victory Tests”, free from the constraints of official Test status, and the combative nature of Ashes competition, consequently produced some of the most exhilarating, free-spirited cricket ever seen in an overwhelmingly celebratory and cordial atmosphere.

And whereas the resumption of sport in present-day times will mostly be driven by the financial imperative/greed, this was sport at its prelapsarian, utopian best. “We were all servicemen,” said Miller, who was then 25 and yet to make his Test debut, “happy just to be alive and fit and well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first “Test” started less than two weeks after Germany surrendered and was held at Lord’s, which staged three of the fixtures due to a debilitated transport system and the fact that few other grounds were usable following the conflict.

Miller, who days earlier had suffered a close shave in his Mosquito during an attack on a German airfield, set the euphoric tone with a century that helped the Australians to a six-wicket win. He scored 105 in the first innings before Australia – chasing 107 in their second innings in 70 minutes – went on to win a thrilling match in the very last over.

In what Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack described as a “cricket celebration” of VE Day, there was a particularly poignant moment which invariably caused Miller to well up until his dying day in 2004.

When one of his team-mates, Graham Williams, walked out to join him at the crease, the 30,000 Lord’s crowd stood as one to applaud the pace bowler as he emerged, haltingly and horribly emaciated after years as a German prisoner of war, through the Long Room and out on to the field. “It was the most touching thing I have ever seen or heard, almost orchestral in its sound and feeling,” said Miller. “Whenever I think of it, tears still come to my eyes.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome 68lbs below his pre-war weight, Williams had to drink glucose and water between overs to keep up his strength. Somehow, in a feat of iron-will and an absolute determination to repay the crowd’s kindness, he scored 53 from 56 balls.

Enthusiasm for the “Victory Tests” snowballed after VE Day, mirroring the national mood and galvanising the country. Rugby, too, would witness its “Victory Internationals”, while football returned in the autumn of 1945, the FA Cup resuming on a mostly two-legged basis ahead of a fully-fledged League programme for the season of 1946-47.

In the summer of 1945, the “Victory Tests” roadshow moved up to Sheffield, which had been bombed by the Germans in December 1940 and was then still a thriving home of Yorkshire County Cricket Club.

The Bramall Lane crowd revelled in a wonderful hundred by Wally Hammond, the 42-year-old England captain, on an opening day when conditions were tricky. Yorkshire’s Len Hutton top-scoring with 46 in the second innings as England won by 41 runs to make it 1-1.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWisden called it “the finest match of the season, played on a natural wicket at the bomb-scarred Bramall Lane”, adding that “about 50,000 people were present during the three days, the receipts being £7,311”. Miller, who failed twice with the bat in that game, led Australia to a four-wicket win in the third match at Lord’s with an unbeaten 71.

Hutton starred for England with 104 and 69 in a series which, for him, had extra significance as he was taking the first tentative steps back after a wartime gymnasium injury that had left his left arm two inches shorter than his right.

“The Victory Series of 1945 provided me with confidence-boosting therapy every doctor would have prescribed,” he wrote in his memoirs. Hutton added that the fixtures “banished any lingering suspicions about my injured arm, the misery of two bone-grafting operations, of 18 months in hospital, and of my arm not being strong enough to hold my first-born son, Richard”.

Miller’s second century of the series followed in the drawn fourth match at Lord’s, which left England 2-1 down going into the final game at Old Trafford. The Manchester ground had also been bombed in 1940, Wisden reporting that, in the build-up to the match, “German prisoners were paid three farthings an hour for painting the buildings (outside) and putting certain parts of the bomb-scarred ground in a safe condition”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith Hutton once more to the fore, top-scoring with a first innings 64, England won a low-scoring encounter by six wickets as the series ended 2-2. “This result,” said Wisden, “which divided the honours, came as a happy conclusion, and everyone could feel contented.”

Summer, though, was not quite over – and nor was the magnificent Miller. In a game between England and the Dominions, also at Lord’s, he scored a swashbuckling 185 in under three hours, smiting seven sixes and lofting one ball on to the roof of the broadcasting box above the England dressing room. Despite twin hundreds in the match from Hammond, the Dominions won by 45 runs with just eight minutes to spare.

Miller’s majestic performance embodied the return of peace, the relief of survival and, above all, of recognising that life is short and should be lived to the full. Looking back on his various adventures in his dotage, Australia’s greatest and glamorous all-rounder– a man once pursued by Messerchmitts, models and marauding bowlers – put it like this: “No regrets. I’ve had a hell of a good life. Been damned lucky."

For more stories from the YP Magazine and The Yorkshire Post features team, visit our Facebook page.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEditor’s note: first and foremost - and rarely have I written down these words with more sincerity - I hope this finds you well.

Almost certainly you are here because you value the quality and the integrity of the journalism produced by The Yorkshire Post’s journalists - almost all of which live alongside you in Yorkshire, spending the wages they earn with Yorkshire businesses - who last year took this title to the industry watchdog’s Most Trusted Newspaper in Britain accolade.

And that is why I must make an urgent request of you: as advertising revenue declines, your support becomes evermore crucial to the maintenance of the journalistic standards expected of The Yorkshire Post. If you can, safely, please buy a paper or take up a subscription. We want to continue to make you proud of Yorkshire’s National Newspaper but we are going to need your help.

Postal subscription copies can be ordered by calling 0330 4030066 or by emailing [email protected]. Vouchers, to be exchanged at retail sales outlets - our newsagents need you, too - can be subscribed to by contacting subscriptions on 0330 1235950 or by visiting www.localsubsplus.co.uk where you should select The Yorkshire Post from the list of titles available.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf you want to help right now, download our tablet app from the App / Play Stores. Every contribution you make helps to provide this county with the best regional journalism in the country.

Sincerely. Thank you.

James Mitchinson

Editor